#AuburnFast is back on the menu

In a shocking turn of events, Auburn’s athletic department has made a competent decision in regard to the football program by hiring South Florida head coach Alex Golesh. Golesh took over a USF program that had gone 1-11 in 2022 under Jeff Scott and immediately took them to a bowl game in 2023, following that up with another 7-win campaign in 2024 and a 9-win season this year, missing out on the championship game in a crowded American Conference.

I want to be up front and say that I would have preferred Jon Sumrall over Golesh. That was my feeling all along and it still is, in spite of how things shook out. That said, Golesh is our guy (and he was in my original top four candidates that I posted before Hugh was even fired, ahem), so let’s take a look at what he brings to the table from an Xs and Os perspective.

Prior to moving to USF, Golesh spent two years as Josh Heupel’s offensive coordinator at Tennessee, running Heupel’s version of the veer-and-shoot offense. Before that, he also worked for him at UCF, running the same system.

I’ve already discussed the veer-and-shoot on the blog before (when Hugh Freeze brought in Philip Montgomery and then scapegoated him for his own terrible coaching), but let’s take another look at the basics of the offense and the unique features of Golesh’s version.

VEER-AND-SHOOT BASICS

The two key components of the veer-and-shoot are pace and space. Obviously most college offenses these days are up-tempo and spread, but the veer-and-shoot takes both of those things to the extreme.

Even by veer-and-shoot standards, though, Golesh’s offenses are fast. His offenses at USF have ranked 2nd, 2nd, and 1st in the country in seconds per play, the best statistical proxy we have for tempo; Tennessee was 1st and 2nd in his two years there as well. It’s safe to say that #AuburnFast is back.

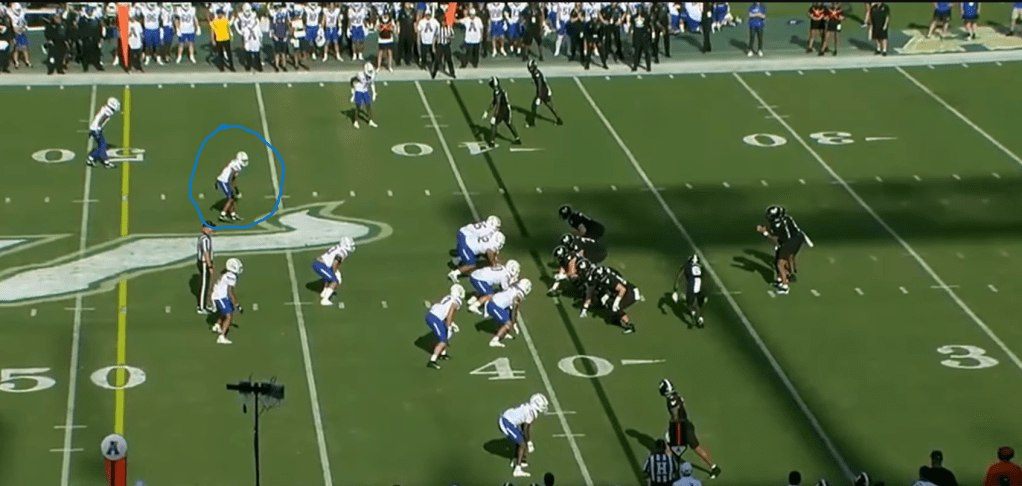

The veer-and-shoot takes spacing to the limit, using all 53.3 yards of the width of the field. This screenshot from USF’s game against Boise in the first week of this season illustrates this well. USF’s outside receivers are lined up almost on the sideline, and even their inside receiver is lined up on the numbers.

This extreme spacing serves two purposes. The first is to isolate defenders, which is illustrated by the receiver at the bottom of the screen. He’s lined up so wide that he’s barely in the picture, but look at the defender lined up over him: there’s nobody in a position where they could possibly help him. The veer-and-shoot loves to exploit these one-on-one matchups by attacking downfield with vertical option routes (more on that later).

The second purpose is to put defenders in conflict. If the defense is going to play a zone or match coverage with two safeties, which the majority of college teams do on the majority of their snaps nowadays, there will always be one player who is responsible for both a zone or a receiver in the passing game and a gap (usually the B gap) in the run game. In this case, it’s the guy standing at the top of the bull logo, whom I’ve circled in blue.

Like many modern spread offenses, the veer-and-shoot makes heavy use of run-pass options (RPOs), which attempt to exploit that conflicted defender by reading him and either handing the ball off if he stays in his pass coverage zone or throwing a route that attacks that zone if he comes down to fill his gap. By using such extreme spacing, the veer-and-shoot maximizes that conflict, forcing the defender to fully commit and making the read easier.

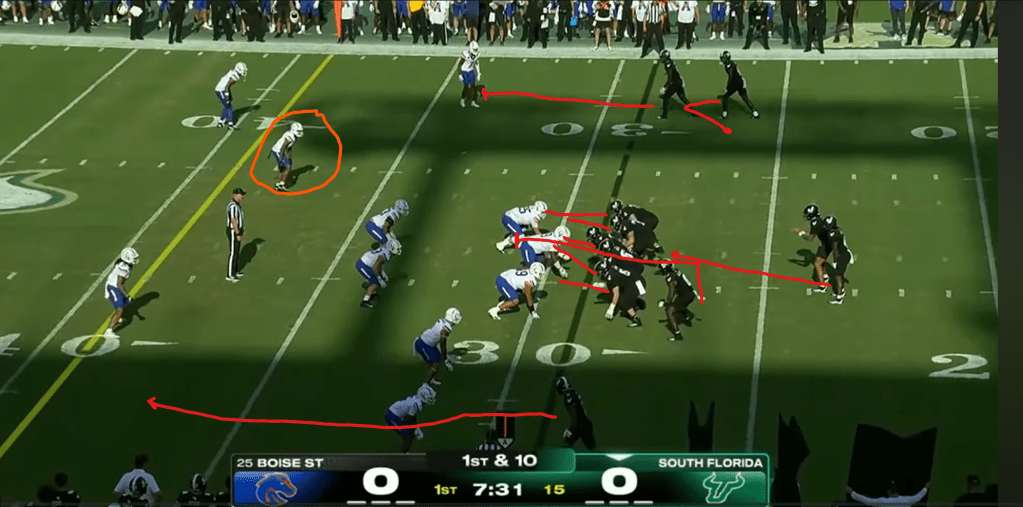

The clip below shows a good example of this, where the conflict player (again the safety lined up on the hash) comes down to fill his run responsibility, and the Bulls’ QB, Byrum Brown, pulls the ball and whips it out to the receiver on a spot screen for a decent gain.

Veer-and-shoot teams have a variety of combinations of runs and pass tags that they can use to attack the defense. Most veer-and-shoot offenses will emphasize quick hitting, downhill runs to maximize the advantage gained from putting defenders in conflict. The faster the run hits, the harder they have to commit to stop it. For the most part, Golesh’s run game consists of inside zone, power, and counter concepts. I’m not going to go into those in detail, but I’ve linked the fantastic WarRoomEagle’s breakdowns from the dearly departed College and Magnolia blog (RIP, comrade).

The pass tags generally consist of quick receiver screens and quick-hitting routes like hitches and slants. Again, I’m not going to break these down in detail, but this post from the veer-and-shoot subreddit (a good resource for additional Xs and Os info) includes some of the most common ones (as well as what I think are Art Briles’ original coaching points and terminology).

So what does the defense do to counter this strategy? Well, the most obvious answer is to bring an extra defender into the box, eliminating the need for the defender lined up outside the box to play a dual responsibility. If you’ve got the dudes to play man-to-man on the outside, then this strategy basically nerfs the veer-and-shoot, if the defense can’t exploit it. This was the problem for Auburn’s knock-off veer-and-shoot during the Philip Montgomery debacle.

Fortunately, competently-run veer-and-shoot offenses that aren’t being undermined by the head coach’s meddling do have effective answers. In the original Briles version of the veer-and-shoot, the answer to this defensive response was usually to throw one of their deep choice routes, which take advantage of the isolation of defenders I mentioned above. This is a play-action pass concept where the playcaller tags one receiver on a deep option route, with the basic rule that “you get one move to get open deep”. This could turn into a vertical route, a fade, a post, or even a curl route if the receiver can’t win deep. The other receivers on that side of the field run routes designed to pull defenders away from the option route and keep that defender isolated. In Art Briles’ version of the offense, the receivers on the other side of the field would take the play off, but Golesh seems to prefer to have them run actual routes.

This is basically a one-read play for the QB, where he’s told before the snap who to throw to. It’s often paired with the aforementioned tempo to try to catch the defense napping or take advantage of them being discombobulated after a big play.

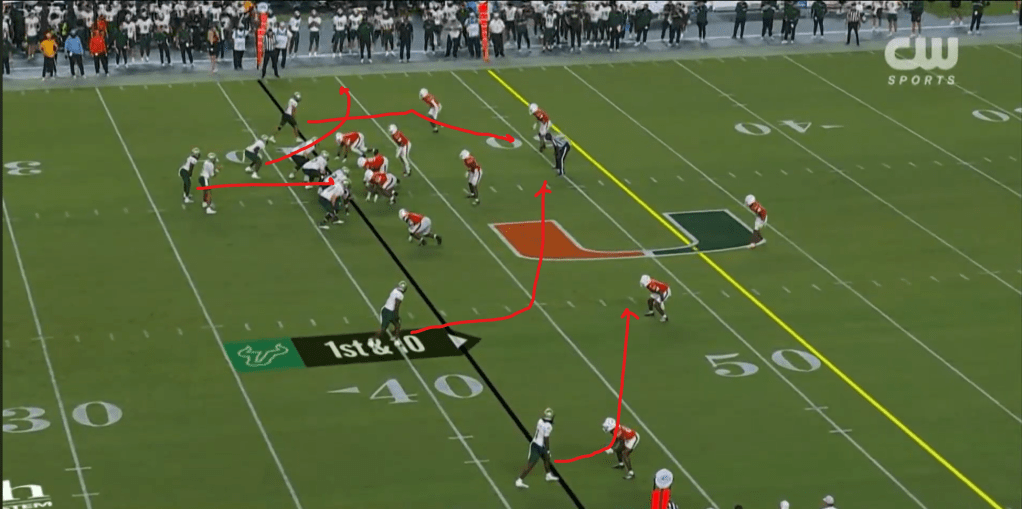

This is a good example of using deep choice routes off of tempo from USF’s game against Miami earlier this year. In this case, they’re running a choice route to the outside receiver at the top of the screen. The inside receiver runs a dig or square-in route designed to occupy the safety, which it does, leaving the outside receiver one-on-one with the CB, and he’s able to beat him deep for a huge gain.

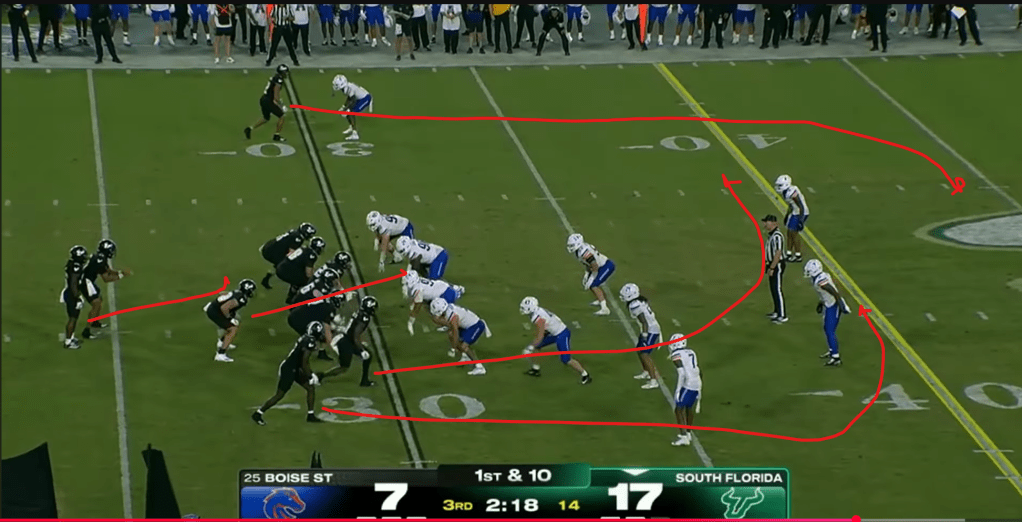

Golesh’s offense, like Briles’, can and does run this concept with any receiver. On this play, they throw deep choice to the single receiver at the top of the field. Here, they’re running it to the single receiver at the top of the screen. The two receivers on the other side run dig routes to pull down the safeties (who were playing kind of shallow at the snap), and this works well; the choice route runner sees this and breaks to the now-wide-open middle of the field on a post route for a big gain into the red zone.

Now that we’ve got a good grasp on the basics of the offense, let’s take a look at some of the unique features, or at least distinctive features, of Alex Golesh’s take on the veer-and-shoot.

UNIQUE FEATURES

The first is another answer to the aforementioned problem of the defense equalizing numbers in the box, which Briles didn’t use that often but which Golesh uses extensively: get the QB involved in the run game.

In this case (the very next play after the one shown above), Boise is playing six-on-six in the box against an 11 personnel set, but the safety on the hash is starting to creep down into the box. USF runs a zone read, in this case, the arc-read version that Gus Malzahn used to great effect during the Nick Marshall era, with the H-back/TE pulling across the formation to block the guy who would usually be responsible for tackling the QB. Byrum Brown gets a pull read from the defensive end here, and he’s able to get outside and tiptoe down the sideline for the TD to blow the game open late in the third quarter.

The next is the use of a variety of dropback passing concepts. The dropback game for Art Briles’ veer-and-shoot was relatively basic, but the use of such wide splits limited what they could do in terms of the dropback passing game, especially over the middle. They ran some shallow crossing concepts, but that was about it.

Golesh, perhaps as a result of working with former Mike Leach QB Josh Heupel, includes more of the air raid-style dropback concepts, including the Pirate’s beloved mesh concept. In this case, it’s a variation on the now-popular mesh-rail version of the concept. The basic idea of mesh is that two receivers will run crossing routes from opposite sides of the formation, passing each other (meshing) to rub off defenders in man coverage. The single receiver and the #3 receiver in the trips run the mesh here; the #2 receiver runs a sit route behind the mesh, and the motion man runs a wheel route on the outside. I’m not sure how Golesh teaches the progression here, but a common method is to have the QB peek the wheel, then look at the sit, and then come down to the mesh as his checkdown. Brown does a good job of getting through his progression, finds one of the mesh runners wide open, and the Bulls should’ve converted on third and medium but got a bad spot, in my opinion.

A final unique feature of Golesh’s veer-and-shoot is his use of compressed formations, which he mentioned in his introductory press conference. This is another way of using space in an extreme way; it’s just the exact inverse of the veer-and-shoot’s typical wide splits. Instead of a maximum stretch on the defense, you’re maximally compressing the defense, which facilitates routes over the middle and getting rubs against man coverage, like the mesh concept above. They especially like to do this when they’re lined up into the boundary and in the red zone, where vertical space is already compressed and their extreme spacing and deep ball threats aren’t as effective.

Here’s an example from the Miami game of the Bulls using a tight receiver split into the boundary. They’re running a common air raid quick game concept, with a slant route from the outside receiver, a flare route from the inside receiver, and double slants on the backside. The compressed formation helps create a rub to get the flare open, but Brown misfires on the throw and it’s incomplete. You get the idea, though.

Next, let’s take a look at the type of personnel that Golesh will be looking for to run this offense, and how Auburn’s existing personnel (pending the portal) might fit into his scheme, and what he’ll be looking for in recruiting.

PERSONNEL REQUIREMENTS

As with most offenses, the veer-and-shoot lives and dies by its quarterbacks. That said, Golesh isn’t necessarily going to be looking for prototypical pocket passers. If you look at the clips above, you can see that his USF QB, Byrum Brown, has a pretty janky throwing motion that is far from NFL ready, but he still put up over 3,000 yards this year. Hendon Hooker was a similar story at Tennessee. The main things Golesh really needs from his QB are a strong, accurate deep ball and the athleticism to make plays in the run game. Hmm, I wonder if Auburn has anyone on the roster who fits that description?

For the wide receivers, there’s only one real requirement.The veer-and-shoot runs on speed, especially out wide. Guys like Jalin Hyatt, who ran a 4.4 at the NFL combine two years ago, was one of the most explosive players in college football when he played for Golesh at Tennessee. Again, does that remind you of anyone on the roster?

One thing Auburn fans will be delighted to hear is that Golesh is something of a tight end guru. After a decade plus of subpar tight end play, hope may finally be on the horizon. Golesh doesn’t necessarily get the tight end involved in the passing game all that much, mostly just RPOs and pop passes, but they’re a major part of the run game, and the very first commit Golesh landed was from a tight end.

I don’t think there’s necessarily a prototypical veer-and-shoot running back, as the practitioner of the offense have had success with big guys, little guys, and everyone in between. Since the offense is primarily focused on inside runs, obviously you need a guy who can take a licking and keep on ticking, but there aren’t really any hard positional requirements.

Finally, in terms of the offensive line, the veer-and-shoot’s reliance on inside zone and power blocking schemes, as well as on play-action pass protection for deep passes, means that you do need some guys with decent size and athleticism up front. This is the main thing that concerns me going into next year, since Auburn’s last truly elite offensive line is more than a decade in the past. We’ll see what Golesh and his staff are able to cook up here.

Before we wrap things up, let’s take a look at some of the potential pitfalls of the veer-and-shoot offense that Auburn might have to contend with.

POTENTIAL PITFALLS

The first major pitfall is the one that Tennessee ran up against in their games against Georgia while Golesh was there. If the other team has the dudes to match you man for man on the outside, they can play with one high safety and eliminate the conflicts and deep threats that the veer and shoot runs on. The QB run game can alleviate this somewhat, but you’re still looking at the same problem I referred to above that plagued Auburn’s 2023 offense. The answer to this problem mostly lies in recruiting, rather than scheme.

The second is the relative lack of complexity in the passing game. Again, this is something Golesh has managed to mitigate by incorporating a more complex, air raid-derived dropback passing game, but the wide splits limit what you’re able to do in terms of the route tree. Those receivers standing almost on the sideline aren’t running many out-breaking routes or crossing routes. You’re also not really able to get many of the rubs I talked about above, which limits your ability to manufacture completions against man coverage. Again, I think Golesh has done better than most of the veer-and-shoot guys in mitigating these challenges, but it’s still something to keep an eye on.

The last major issue I see is the #narrative that the offense doesn’t prepare QBs for the NFL, which isn’t a problem for the offense itself so much as it is in recruiting, where opposing coaches who run more of a pro-spread style of offense can hit you on it. Usually I would dismiss this as nothing more than talking head nonsense, but the fact of the matter is that there hasn’t really been a veer-and-shoot QB who’s gone on to have sustained success in the NFL, including Golesh’s best QB, Hendon Hooker. Now, to be clear, a college coach’s job is to win college football games, not serve as a farm system for the NFL, but this is something that will be used against you as a negative recruiting tactic. That said, you’re not necessarily fighting for the same types of QBs as the guys running more pro-style offense, so you can mitigate the damage caused by this #narrative somewhat.

That’s all I have for now. I’ll likely be back with more of a proper preview in the spring once we have a better idea of what the roster is going to look like, but things should be fairly quiet here for the next few months.

SOME ADDITIONAL VEER AND SHOOT RESOURCES:

Kendal Briles’ install sheets from when he was at Florida State in 2019 (a rarity because Briles the elder was notoriously secretive about his offense)

Part I of Ian Boyd’s two-part series on the veer-and-shoot (paywalled but his newsletter is worth it, imo)

Leave a comment